Eugenics: Its Origin and Development (1883 - Present)

Eugenics is an immoral and pseudoscientific theory that claims it is possible to perfect people and groups through genetics and the scientific laws of inheritance. Eugenicists used an incorrect and prejudiced understanding of the work of Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel to support the idea of “racial improvement.”

In their quest for a perfect society, eugenicists labelled many people as “unfit,” including ethnic and religious minorities, people with disabilities, the urban poor and LGBTQ individuals. Discussions of eugenics began in the late 19th century in England, then spread to other countries, including the United States. Most industrialized countries had organizations devoted to promoting eugenics by the end of World War I.

To better understand and protect against current and future discriminatory trends that misuse genetics and, through its association, genomics, this timeline highlights key moments in the development of eugenics, with a focus on the American eugenics movement.

Timeline — select a year for more details

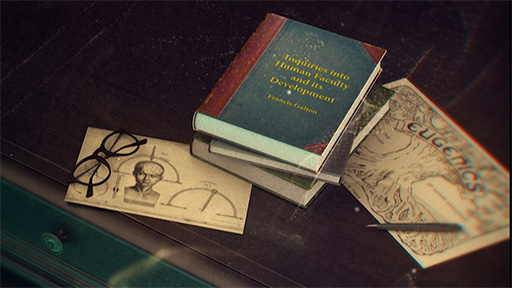

Galton defines eugenics and gives birth to a movement

Francis Galton (pictured), Charles Darwin’s cousin, derived the term “eugenics” from the Greek word eugenes, meaning “good in birth” or “good in stock.” Galton first used the term in an 1883 book, “Inquiries into Human Fertility and Its Development.” Francis Galton (pictured), Charles Darwin’s cousin, derived the term “eugenics” from the Greek word eugenes, meaning “good in birth” or “good in stock.” Galton first used the term in an 1883 book, “Inquiries into Human Fertility and Its Development.”

We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea.

Galton believed that eugenics could control human evolution and development. In his writings, he argued that abstract social traits, such as intelligence, were a result of heredity. In his book, he claimed that only “higher races” could be successful. Galton’s writings reflected prejudiced notions about race, class, gender and the overwhelming power of heredity.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Eugenics societies begin to form globally

The work of German biologist Alfred Ploetz, who coined the term “racial hygiene,” had a significant influence on Nazi race-based eugenics. In 1904, he founded the “Archiv für Rassen - und Gesellerschaftsbiology” or Archive for Racial and Social Biology, the first journal that focused primarily on racial hygiene and eugenics. The journal emphasized Nordic and Aryan racial superiority. The Society for Racial Hygiene, founded in 1905 in Germany, grew from this idea and became the earliest eugenics-focused organization in the world. Other similar organizations, like the Eugenics Education Society (now the Galton Institute) in Britain, were founded around this time. A paraphrased propaganda poster for the Nazi T-4 Euthanasia program (pictured) states, “This hereditary defective costs the people's community 60,000 Reichsmarks for life. Compatriot, that's your money, too!”

Timeline — select a year for more details

American Breeder’s Association establishes a Committee on Eugenics

The American Breeders Association was the first U.S.-based organization to study and promote genetics as well as plant and animal breeding research in the United States. At the request of Charles Davenport (pictured), a prominent biologist at Harvard University, the association created a committee to study eugenics.

Davenport is considered the most important eugenicist in the United States. He was an outspoken racist who believed that abstract traits like intelligence had strict hereditary links. Davenport used the association’s Committee on Eugenics to study his ideas of selective and restrictive breeding in humans. He also used the committee to promote future eugenics-minded organization efforts.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Indiana passes first sterilization law; other states follow

After previous efforts by Michigan and Pennsylvania failed, Indiana became the first U.S. state to pass a compulsory sterilization law. Indiana’s law mandated sterilization of those in state institutions who were deemed “idiots” or “imbeciles,” as well as certain classes of criminals. Under this law, women were sterilized for being deemed “feebleminded” or “promiscuous.” By the late 1800s, state officials were increasingly convinced that the social problems of crime and poverty were genetically inherited. In his 1881 article entitled “The Tribe of Ishmael: A Study in Social Degradation,” the influential Indiana preacher Oscar McCulloch wrote, “[N]ote the force of heredity. Each child reverts to the same life, reverts when taken out.”

The Indiana law was in effect from 1907 to 1974. During that time, approximately 2,500 people were forcibly sterilized. Soon after Indiana passed their law, other states adopted similar legislation. By the 1930s, over 30 states had sterilization laws. As a result, more than 60,000 persons were sterilized before these laws were overturned. (Graph depicting cumulative record of sterilizations in U.S. from 1907-35 is pictured.) Some U.S. sterilization laws remained in place until the 1980s.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Davenport establishes the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Through funding by philanthropist Mary Williamson Harriman and cereal magnate John Harvey Kellogg, Davenport started the Eugenics Record Office (pictured) at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York. The office was an extension of an experimental station that Davenport had previously started in 1904 at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory as part of the Carnegie Institute of Washington. The station’s initial purpose was to study Mendelian inheritance patterns and breeding in animals; however, the office focused specifically on humans and eugenics.

The Eugenics Record Office sent out questionnaires to families, created pedigree charts and trained fieldworkers who traveled across the country to compile data on traits like “feeblemindedness,” “criminality” and “alcoholism.” The office housed data on thousands of individuals and families. It also tried to educate the public about the values of eugenics. Its publication, Eugenical News, was distributed nationally and included information about eugenics research, fertility and other related issues. Some of the most important scientists of the day supported the Eugenics Record Office, including Nobel Laureate Thomas Hunt Morgan (though he later became an outspoken critic of eugenics) and Alexander Graham Bell.

Timeline — select a year for more details

First International Eugenics Congress takes place

The First International Eugenics Congress, organized by the British Eugenics Education Society, was held in London in 1912. Leonard Darwin (pictured in the top right), who was Charles Darwin’s son, presided over the event. Over 400 people from across Europe, Britain and the U.S. attended, including Winston Churchill, Arthur Balfour and Alexander Graham Bell. Several well-known geneticists also attended, including Reginald Punnett, who created the Punnett Square. Punnett said, “The one instance of eugenic importance that could be brought under immediate control is that of feeble-mindedness. Speaking generally, the available evidence suggests that it is a case of simple Mendelian inheritance.”

The American Breeders Association sponsored the exhibit by the U.S. eugenicists. Davenport, statistician Raymond Pearl and agricultural geneticist Bleecker Van Wagenen attended. Van Wagenen later presented a report to Congress summarizing recent laws implemented in various states to sterilize the “unfit.”

Timeline — select a year for more details

Eugenics organizations expand globally

The development of theories of biology and heredity, in addition to the cataclysmic events of World War I, caused a renewed interest in using eugenics to improve society. Eugenics organizations had been founded in the United States, Hungary, France, Italy, Argentina, Mexico and Czechoslovakia by the end of World War I. While each of these organizations were specific to their countries, they committed to the principles and practices of eugenics. The American eugenics movement focused on sterilizing the “feebleminded” while also promoting the racial ideology that white Anglo-Saxons were the “superior” race. A document presented by the Cuban delegation at the first Panamerican Conference on Eugenics and Homoculture is pictured.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Kansas holds first Fitter Family Contest

The Fitter Families for Future Firesides, otherwise known as the Fitter Family Contest, grew out of Better Baby Contests. Better Baby Contests started in 1908 and were held at state fairs nationwide. Judges would grade children ages 6 to 48 months on their physical appearance and their supposed mental capacity. The first Fitter Family Contest was held at the Kansas State Free Fair. (The winning family is pictured.) Mary T. Watts, a Parent-Teacher Association member, and Florence Brown Sherbon, a U.S. Children’s Bureau fieldworker, organized the event.

While the Better Baby Contests were not explicitly tied to eugenics, eugenics institutions such as the Eugenics Record Office sponsored the Fitter Family Contests. These contests were held across the country throughout the 1920s. Participating families were required to submit a record of family traits. Doctors at the events then performed physiological and psychological tests on family members to determine their overall “eugenical worth.” The winning families were almost always white, reflecting the ideals of the larger eugenics movement in the United States.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Second International Eugenics Congress is held in New York City

The American Museum of Natural History held the Second International Eugenics Congress in New York City in 1921. (The congress exhibit hall is pictured.) Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the museum, presided over the congress, and the Eugenics Record Office sponsored it. Attendees came from Europe, the United States and Central and South America. Immigration issues accounted for most of the discussions at the congress. American eugenicists, such as Eugenics Record Office Director Harry H. Laughlin, used their findings to support the argument that European immigrants were inferior and that their birthrates represented a threat to the Nordic races.

Genetics was also a prominent topic at the congress. The exhibits emphasized the role that Mendelian genetics played in the eugenics movement. One exhibit contained portraits of famous eugenicists, which included important figures in the history of genetics such as Gregor Mendel, Erich von Tshermak and Hugo De Vries. Another was entitled “Genetics: Principles of Heredity in Animals and Plants.” Davenport invited William Bateson, who founded and named the field of genetics, to the congress. Bateson declined, writing: “the real question is whether we ought not to keep genetics [and eugenics] separate.”

Timeline — select a year for more details

U.S. President Calvin Coolidge signs the Johnson-Reed Act

In the early 20th century, immigration was a key political issue in the United States. Most immigrants came from non-English-speaking countries, such as Italy and Poland. These new immigrants mostly settled in cities where people believed overcrowding strained the urban infrastructure. An illustration for article "An Alien Anti-Dumping Bill" in The Literary Digest from May 7, 1921, is pictured.

Eugenicists, including Laughlin, saw these new “non-Nordic” immigrants as undesirable compared to immigrants from northern Europe, and he spoke about the inherent criminality of non-Nordic immigrants before the U.S. Congress in 1921. His testimony was key in the passing of the Johnson-Reed immigration Act in 1924. The act placed a quota on the number of immigrants to the United States from Southern and Eastern Europe, and completely excluded Asian immigrants. This act allowed for more immigration from northern European countries.

Timeline — select a year for more details

The American Eugenics Society is established

The American Eugenics Society grew out of a committee formed at the Second International Eugenics Congress in New York. It was formally established in 1926 by several prominent American eugenicists, including Eugenics Record Office Director Laughlin; Madison Grant, author of the book The Passing of the Great Race, whom Adolf Hitler admired; and Irving Fisher, Yale University economist. The American Eugenics Society exhibit at the Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia is pictured.

The American Eugenics Society’s primary function was to educate people about the importance of eugenics. It sponsored events at local and state fairs, such as Fitter Family Contests, and exhibits that illustrated Mendel’s laws of inheritance and showed the economic costs of caring for “mentally ill” children. It distributed several publications, including Eugenics, Eugenical News and Eugenics Quarterly. At its height in the 1930s, the organization had more than 1,200 members, including notable names like Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Buck v. Bell County

In 1924, Virginia’s General Assembly passed the Eugenical Sterilization Act, a law designed around model legislation that Laughlin had created. The law allowed the commonwealth of Virginia to forcibly sterilize those deemed “intellectually disabled.” The same year, Albert Priddy, the superintendent of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, requested the authority to sterilize an 18-year-old patient, Carrie Buck (pictured with her mother). Her mother had a history of prostitution, and Buck had been raped by a relative and subsequently birthed a child. Buck was committed to the State Colony and deemed “feebleminded.”

The legal case to sterilize Buck made it to the Supreme Court, who decided in an 8-1 vote that it was in the commonwealth’s best interest to proceed with the sterilization. Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes wrote the majority opinion, saying, “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Timeline — select a year for more details

Third International Congress of Eugenics is held

Fewer than 100 delegates attended the third (and final) International Eugenics Congress. (The congress exhibit hall is pictured.) By the 1930s, many prominent scientists were openly critical of the scientific merits of eugenics. Among them were some who had previously been supportive, including geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan and statistician Raymond Pearl. These critics pointed out the eugenicists’ flawed experimental methods, their overly simplistic application of Mendelian genetics and their racist and classist biases. Geneticist Herbert Jennings criticized the beliefs that European immigrants were more prone to being criminals than other types of immigrants.

Some critics within the eugenics community also attended the congress. They argued that Davenport and Laughlin did not sufficiently account for the effects of economics and environment in their studies.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Eugenics Record Office closes

With the onset of World War II in 1939, eugenics continued to fall out of favor with both the public and the scientific community. Throughout the 1930s, the U.S. population learned how scientists and politicians in Nazi Germany advocated for and implemented eugenics policies, such as forced sterilization against Jews and persecuted minorities, and that such practices were inspired by policies in many U.S. states. As these horrific realities became more known, eugenics became increasingly unpopular in the United States. In 1935, the Carnegie Institute of Washington assembled a committee of scientists to study the validity of the eugenics research supported by the Eugenics Record Office (pictured). In 1939, Vannevar Bush, the president of the Carnegie Institution, cut funding to the Eugenics Record Office, which led to its closing in December of that year.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Eugenics in the post-war period

Eugenics adapted and changed after World War II. Most U.S. academics and scientists in the eugenics community distanced themselves from the eugenics movement in Germany. Many eugenicists became advocates of neo-Malthusianism, the belief that global population should be reduced to prevent mass starvation and societal collapse. Some of them went on to lead prominent population research organizations in the United States. For example, Robert Cook (pictured, former editor of the Journal of Heredity, board member of the American Eugenics Society and population consultant to the National Institutes of Health) was president of the Population Reference Bureau.

Some geneticists, including Curt Stern and Theodosius Dobzhansky, reformulated their defense of eugenics based on an improved knowledge of human genetics and an added emphasis on individual choice and autonomy. However, they still believed that people with “serious hereditary defects” should be placed in institutions and, in some cases, involuntarily sterilized if they resisted social pressure to not have children.

Timeline — select a year for more details

Oregon is the last state to repeal its sterilization law

Many states repealed their sterilization laws decades after World War II. Virginia repealed its Eugenical Sterilization Act in 1974. California, which sterilized more than 20,000 people, repealed its law in 1979. In 1983, Oregon became the last state to repeal its sterilization law. By that time, 2,648 people had been sterilized in the state. It took nearly 20 years after Oregon’s repeal for Virginia to formally apologize for the sterilization of Carrie Buck (pictured).

Timeline — select a year for more details

The Bell Curve and modern concerns about a resurgence of eugenics

Richard Hernstein and Charles Murray published The Bell Curve in 1994, which promoted historical eugenic arguments. These authors argued that genetics determined intelligence and social mobility in American society and that genetics caused African Americans and European Americans to have different IQ scores.

James Watson was the former director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, former director of the National Center for Human Genome Research (now the National Human Genome Research Institute or NHGRI) and key figure in the Human Genome Project. Repeatedly since 2000, Watson has made comments that publicly support the scientifically racist claims in The Bell Curve and other works. Watson’s opinions on these topics are counter to the NHGRI’s mission and values.

Recently, groundbreaking technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9, have raised concerns about using genome editing methods to make genetic enhancements. In response, some prominent geneticists have publicly requested to stop such enhancements.

Eugenics remains a constant issue in society and the scientific community, and the NHGRI is committed to monitoring its presence and confronting its inaccuracies. (The Nature cover announcing the completion of Human Genome Project is pictured.)

Last updated: November 30, 2021